By now, everyone knows about the phenomenon of fake news. But it’s not only news that’s faked online. Researchers have been tracking the underground world of spammers and scammers for years and coming up with strategies to identify it. But as Robbie Harris reports, it’s not clear when or if they’ll ever be able to stop it.

Whether it’s faked restaurant reviews, unreliable stock tips, or opinion spam, online trickery has caused untold numbers of people to buy, think, or do something they might not otherwise have.

Gang Wang recently joined the computer science department at Virginia Tech. He’s designed security breach detection systems for industry and users trying to stay one step ahead of the attackers.

But what he saw is that this is a cat and mouse game.

"When you have some defense, upgraded attackers will do something to counter that,” he says. "And because the machine and humans are working together, those attacks become harder to detect."

Early on, Wang says, much of Internet scamming involved your simple 'attack of the robots.' The white hats pretty quickly came up with solutions like blacklisting a site that was clearly being directed by no human hand. They were easy to detect because of the high number of hits from a single URL.

And how do they fight back? By using robots of their own for a kind of bot on bot game that, for the most part, became a stalemate.

“This is when attackers realized machines can not do it all," Wang says. "So they decided, 'Let’s put humans in the loop and try to upgrade the attacking weapon.' So with the recent development of artificial intelligence, not only are good people using that for good purposes, bad people are using it for bad purposes too.”

Robotic attackers have a built in tenacity to spam ad infinitum, but they’re not yet experts at natural language. It’s humans who have the creativity to craft more believable posts - ones that other humans might not immediately flag as fraudulent.

“And because the machine and humans are working together, those attacks become harder to detect," says Wang.

During the recent election, we heard about click farms in Macedonia where people were paid by the post to disseminate fake news. Several years ago, Wang’s research uncovered vast underground markets doing something similar.

The trick was to have a human step in at precisely the right time to assist the robots in their posting frenzy.

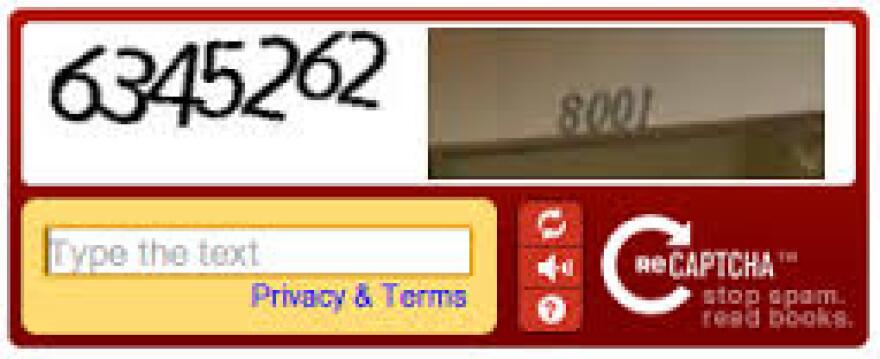

It’s at the moment when a machine sees that box with the letters in it, that you need to type, to prove you’re not a robot - the thing called CAPTCHA which stands for "Completely Automated Public Turing test to tell Computers and Humans Apart.”

It's named for the legendary Alan Turing, who is considered the father of computer science. To pass the test, a computer must be indistinguishable from a human - to another human.

“There are large CAPTCHA farms that have been discovered in third world countries, these South Asia areas, where people are hired to work in front of their computer to solve those kinds of CAPTCHAs in real time. So what happens is, when the Botnets are attacking, attacking, attacking..."

Wang says the best defense in the cat and mouse game of cyber scamming is to find ways to continue to increase the costs to the scammers.

“If a service has built security mechanisms that can cause a really high cost for the attackers to by-pass, they will just reconsider whether they want to do the attack or not,” he says.

But right now, scammers have the advantage. Wang says the CAPTCHA farms his team studied amounted to a multi-million dollar industry - not annually, but monthly.